Practical Ergonomics

for the quarantined computer worker

for the quarantined computer worker

What are ergonomics?

Ergonomics is the science of designing and arranging the things people use so that the people and the things interact in a way that is health, safe and efficient.

Why should you care?

The problem with ergonomics as a science is that often the theoretical ideal chair or sitting position doesn’t match up with what’s actually comfortable. And most of us aren’t going to follow ergonomic guidelines that don’t take comfort into account, even if it ends up creating problems down the road.

So instead of focusing on purely scientific ergonomics, we are going to talk about practical ergonomics.

Practical ergonomics takes into account the fact that:

When it comes to working at a computer there is no perfect ergonomic design. Abstinence is the only sure-fire solution.

Since that’s rarely an option, we can make the best of an imperfect situation by applying practical ergronomics, which involves some basic knowledge and a lot of common sense. These principles are neither difficult nor overly time-consuming to implement. With small amount of planning, the common-sense application of these principles can help you work more comfortably, be less crabby at the end of your day, and avoid developing painful structural and functional conditions.

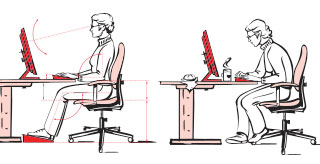

Standing workstations are great, but most people, especially when working from home, will find themselves working at their computer in a chair.

Seated posture causes higher disc pressure than standing or lying down. Spinal ligaments are under less tension when you’re seated, and this results in a lot more muscle activation to maintain spinal stability.

In a rough order of importance, here are some things you should consider if you want to improve your seated position:

A support behind your lower back allows those muscles to relax and can make a big difference in comfort and fatigue throughout the day.

If your chair is countoured nicely, you may find you don’t have to add anything at all. But if you’re a smaller person and the depth of the chair seat is too great, you’ll find that you have to sit forward in your chair. In this case, a contoured lumbar support pillow is great if you have one, but most people don’t. Finding the right combination of pillows, blankets, etc to place behind your lumbar spine can provide the support necessary to allow spinal muscles to relax.

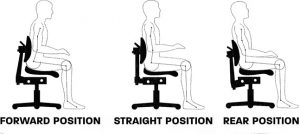

When seated your pelvis rotates posteriorly and the main points of support are the ischial tuberosities (your “sit-bones”, “butt-bones” ,whatever you want to call them). The center of gravity of your upper body can either be in front, directly over, or behind the ischial tuberosites.

In most cases the best position to strive for is one in which your center of gravity is in the middle position, directly over the ischial tuberosities. In this position about 25% of your body weight is transmitted through your feet on the floor and your lumbar spine is either straight or in a slight kyphosis, which is about as close to ideal as you’re going to get in a seated position.

It’s common to have your center of gravity in front of the ischial tuberosities while working seated. Try shifting your center of gravity back a bit and see how it feels. Repositioning your chair and other workspace items can allow you to change your seated center of gravity, and you may find that this makes a difference over the course of your workday.

There’s not much you can do about this if your chair isn’t already designed this way, but it’s worth mentioning for the next time you’re out shopping for a new office chair. One of the reasons airplane seats are so uncomfortable is because they lack this feature. Even if the seatback has a contoured lumbar support, you can’t take advantage of it if you can’t slide your rear back far enough. As a result, your lumbar spine ends up being forced into a flexed position when you sit back in the chair, and this increases disc pressure and typically leads to a sore back. Adding some extra lumbar support behind your back can help mitigate this problem.

A lot of these factors end up affecting one another. The depth of the seat bottom is going to determine if you can sit back far enough in your chair to utilize the backrest. If you’re a smaller or shorter person you’ll be forced to move forward if the seat bottom is too deep, either due to your legs not being able to reach the floor or because of pressure from the front edge of the chair on the poplieal fossa (fancy name for knee-pit). In either case you lose the support of the backrest, and might as well be sitting on a stool. Here too, your solution will be to put some thought into adding extra lumbar support behind your back.

Ergonomically speaking, it’s best to sit with your thighs approximately parallel to the floor and your feel flat on the floor. In this position your feet are going to give help give your rear a break by supporting a portion of your seated body weight. This can make a big difference in terms of comfort all by itself, and if your chair has the ability to incline the seat bottom, it pays to toy around with a slight incline to vary the amount of force diverted to your feet.

That being said, it’s important to keep in mind that the goal shouldn’t be to find a single posture to assume for the entire workday. You should be familiar enough with your chair to be able to readjust it regularly in order to redistribute loads. Having enough space under your chair to move your feet and legs freely helps to accomplish this as well.

Fine-tuning seated ergonomics would be a lot easier if all you had to do was sit in your chair. When you start to add a keyboard, mouse, monitor, document holder, webcam, and the rest of the stuff you actually need to use for work, things get messy.

The goal of practical ergonomics is not perfection, it’s just making things less messy. One way to do that is to keep in mind a few guidelines to help bridge the gap between your chair and your stuff.

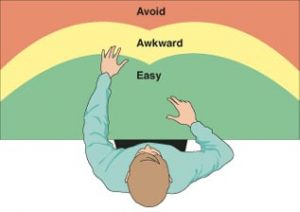

1. Arm position

Your arms are literally the bridge between your chair and your stuff. Ideally you want to be able have your arms hanging naturally at your sides with your elbows about about 90 degrees. If your arms aren’t hanging at your sides, you’re activating the muscles of your shoulder girdle and neck to support your arms. This inevitably leads to neck problems, tight shoulders, and painful trigger points in muscles like the upper trapezius and scalenes.

If the desk or table you’re working at is too high or low for your arms to be able to hang naturally at your sides, see if you can find a different surface to work on, or adjust the height of your chair. This can especially be a problem if you’re a shorter person. One way to try solving this is by finding something to use as a footrest so that you can raise your chair without having your legs dangling.

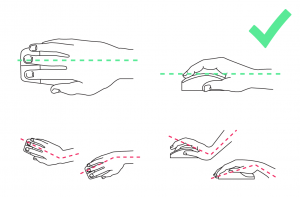

You also want to try to keep your hands roughly in line with your forearms so that your wrists aren’t flexed or extended. If you can adjust the height of the armrests on your

You also want to try to keep your hands roughly in line with your forearms so that your wrists aren’t flexed or extended. If you can adjust the height of the armrests on your chair, take advantage of this feature and adjust them to a supportive height. Alternatively, consider using a palm or wrist rest of an appropriate size for your keyboard.

chair, take advantage of this feature and adjust them to a supportive height. Alternatively, consider using a palm or wrist rest of an appropriate size for your keyboard.

Also pay attention to where you place your keyboard, mouse and other frequenctly used items. Keeping your repetitive forward reaches short can make a big difference over the course of a workweek.

Computer display placement is one of the major factors that influence head and neck posture. The two main variables to keep in mind here are: 1) forward head position, and 2) head flexion.

The farther you head moves forward, the more strain you place on your cervical spine. Likewise, the more you flex your head foward/downward, the greater the loss of cervical lordosis (the normal neck curvature) and the greater the increase in disc pressure and muscle activation.

Even a small downward flexion of your head can be significant. Set your monitor height so that you’re looking straight ahead (or even at a very slight upward angle). I use Robbins’ 3.5″ thick Pathological Basis of Disease textbook to accomplish this because if I don’t, I get a lot of discomfort between my shoulder blades.

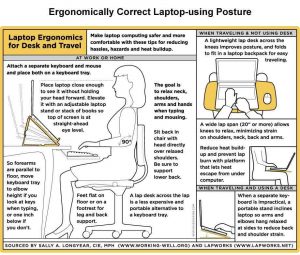

Laptops are a problem. They’re terrible if you have to spend any significant amount of time on your computer, and you’re just asking for problems if you use them on a regular basis for work. Solution #1 is to hook up an external monitor.  That’s the best solution.

That’s the best solution.

If that’s not possible, solution #2 is to stack a whole lot of books under your laptop to get it up to the correct height. At which point you’re going to realize that you need an external keyboard and mouse to make this work.

If solution #2 isn’t possible, take the time to adjust the laptop display’s angle, brightness, contrast and other settings so that you can work with the least amount of anterior head carriage and flexion as is possible. Experiment with setting the keyboard at an angle and using a palm/wrist rest as well.

In addition to your computer display, pay attention to how you’re arranging any documents that you have to work with. If possible, try to place document holders at the same distance, height and angle as your computer monitor. If you find yourself contantly going back and forth between viewing a document and your computer screen, it is far easier on your eyes to have them at the same distance so that you don’t have to refocus between objects. It goes without saying that a good lighting environment helps prevent mental fatigue as well.

The best posture and ergonomic setup is the one that is most comfortable and which can be maintained while taking into account some of these basic guidelines. If you find yourself haphazardly dumping all your stuff on the desk and plopping down in a chair that you haven’t adjusted to fit your physique, you’re doing it wrong.

But it’s not about measuring angles and adopting a militaristic posture either. A basic awareness of your working environment coupled with the common sense application of these basic guidelines can improve both the comfort and safety of most at-home work environments.

As with most things, half the battle is motivating yourself to take the time to do it, which might be as simple as asking yourself a question like: “Do I want to encourage the growth of that little hump at the base of my neck?”